Edison: Practical Futurism

"Vision without execution is hallucination" - Thomas Edison

Tao of Founders is now available in audiobook on Spotify and Audible!

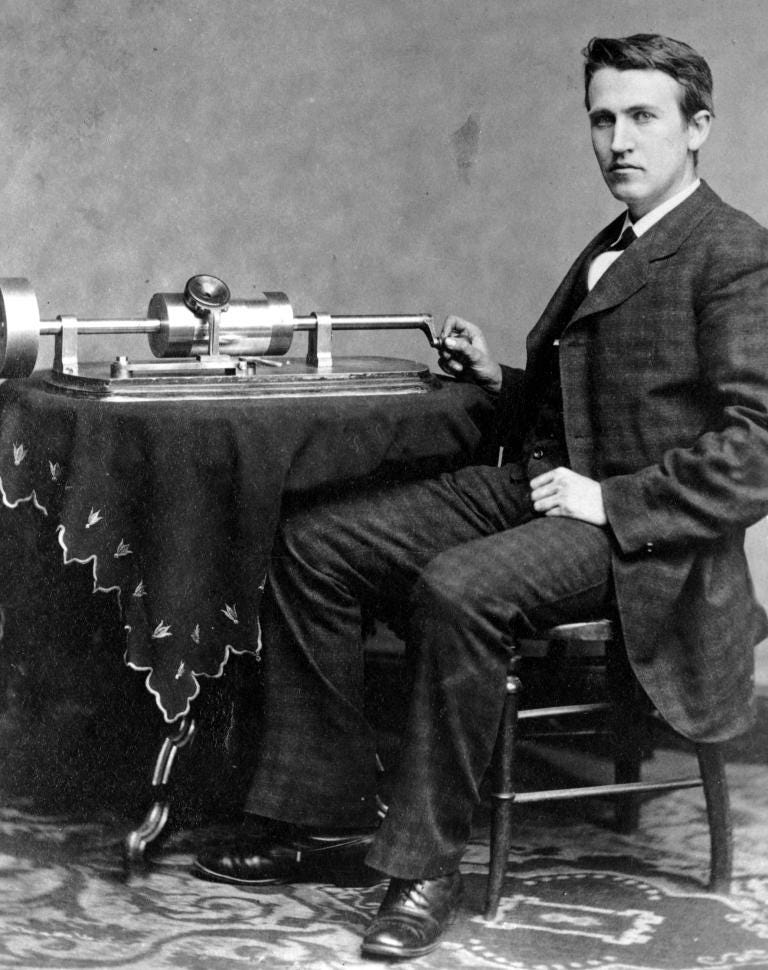

Thomas Edison pioneered the systematic industrialization of innovation. He created the world's first true research and development laboratory and made innovation a team sport - unlike many inventors of his era who worked alone. Edison believed that invention could be codified and organized as a process rather than relying on eureka moments (ironic, for the guy who invented the lightbulb).

This systemized approach—teams of specialists working in coordinated fashion—created an innovation pipeline that could simultaneously pursue multiple inventions while methodically testing thousands of approaches in rapid fashion, essentially inventing the modern corporate R&D function. Edison and his team went on to register over one thousand patents between 1865 and 1931. His electrical lighting company went on to become General Electric.

"To have a great idea, have a lot of them."

Edison practiced what might be called practical futurism—pursuing visionary concepts but always with clear paths to immediate implementation. Unlike purely theoretical inventors or futurists who imagined technologies without creating them, Edison insisted on bringing ideas into physical reality regardless of how revolutionary they seemed. This practical materialization of future possibilities—making the theoretical tangible—allowed him to create functioning versions of technologies others only could theorize about.

Adversity as Opportunity

At around age 12, Edison suffered from scarlet fever which, combined with untreated middle ear infections, caused significant hearing loss. Rather than viewing this as purely a disability, Edison later reflected: "My deafness has not been a handicap but a help to me... It has saved me from having to listen to reasons why things can't be done."

"Our greatest weakness lies in giving up. The most certain way to succeed is always to try just one more time."

This early adversity shaped his perspective on limitations—teaching him to reframe apparent disadvantages as potential strengths. His partial deafness allowed him to concentrate deeply without distraction during experiments, a capacity he credited for much of his productivity (being extremely stubborn also probably helped). I suspect Edison would not have gained the tenacity needed to fail for a living if he had not encounter limitations early on in life. He understand how to direct his mind and energy to get results.

"The first requisite for success is the ability to apply your physical and mental energies to one problem incessantly without growing weary. When you have exhausted all possibilities, remember this: you haven't."

In 1869, Edison arrived in New York with just $1 in his pocket after his previous telegraph-related inventions had yielded little financial success. A fortuitous opportunity arose when a stock ticker in a brokerage office malfunctioned during a financial crisis. Edison, who happened to be present, fixed it on the spot. Impressed, the owners hired him to maintain their equipment. This led to Edison's improved stock ticker invention, which he sold to the Gold & Stock Telegraph Company for $40,000—a substantial sum at the time. Edison recalled: "I had made up my mind to two things: I would be paid for my inventions, and I would do my own manufacturing." This experience shaped his belief in controlling both the creative and business aspects of invention. Both are needed for inventions to take off, a contrarian view during Edison’s era. Incidentally, this non-dual approach to invention made him unique - and led him to approach problems in a way others couldn’t.

Patent #1

Edison's first patented invention was an electronic vote recorder for legislative bodies. Though technically sound, it was rejected by politicians who explained that slower voting was actually preferred because it allowed time for lobbying and deal-making.

I realized the importance of understanding not just how something works, but how people will use it."

This experience fundamentally shifted his approach—he vowed never again to invent something without first ensuring a market existed for it and people would use the invention, an insight that guided his subsequent work on telegraph improvements, phonographs, and light bulbs.

"The value of an idea lies in the using of it."

Edison pioneered a unique approach to market-informed experimentation, using public reaction to guide technical development. He used the art of the demo to gauge user interest and demand. When demonstrating early phonographs, he carefully observed audience reactions to different aspects of the technology, then adjusted his development priorities based on which features generated the most enthusiasm. "Anything that won't sell, I don't want to invent," he maintained. This integration of public response into the invention process— early user testing—enabled him to focus resources on aspects with the greatest potential impact.

Storytelling overcomes resistance to change

Edison demonstrated unusual insight into the relationship between media and technology, understanding that public perception shaped adoption. He staged dramatic demonstrations of his inventions, like lighting up Menlo Park at night to showcase electric lighting, and used newspapers effectively to build anticipation for new technologies. "Advertising is the life of business," he noted. This integration of technological development with public narrative—essentially creating storylines for his inventions—accelerated adoption of his innovations beyond what technical superiority alone would have achieved.

"The problem with innovation isn't the innovation itself, but with how people react to change.

Products co-evolve within large systems

When developing electric lighting, he didn't just create a light bulb but designed an entire electrical distribution system including generators, wiring standards, meters, and safety systems. Edison faced enormous skepticism about the practicality of his direct current (DC) system for urban use

Rather than just inventing a light bulb, he set out to create an entire electrical distribution system. He fully understood his invention would be met with resistance to change unless he could design the right systems around the product he sold. The Pearl Street Station became the first commercial power plant in the United States when it opened in 1882, initially serving just 59 customers in lower Manhattan.

Edison maintained a distinctive economic perspective, focusing on how innovations might reshape entire economic systems rather than simply generate profits. When developing electric lighting, he calculated that electric illumination would need to cost less than gas lighting to drive adoption, then worked backward to achieve that economic target. "We will make electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles," he declared.

Failed experiments often find accidental users

“Just because something doesn't do what you planned it to do doesn't mean it's useless”

Many modern inventions were initially intended to solve another problem: post-it notes, LSD, microwaves, Viagra, WD-40, Play-Doh, Bubble Wrap. After experiencing setbacks in the mining and ore milling business, Edison applied his knowledge of materials and crushing equipment to the cement industry. Using knowledge from his failed ore separation business, he revolutionized cement production with rotary kilns and other innovations. Edison was keen to challenge his own flawed assumptions and avoid remaining attached to what he thought he knew, enabling him to reinvent successfully.

Have a nice week end!